“Because so much of the curriculum and teaching methods employed in most schools are based on the needs of this mythical average student, they are also laden with inadvertent and unnecessary barriers to learning.”

Anne Meyer, Universal Design for Learning: Theory and Practice

Teaching Philosophy

As a person with a disability, I am keenly aware of the vital role accessibility plays in effective teaching. Even the best curriculum will fail if it is not accessible to students. As a student, I spent years confronting the barriers to accessibility that are often inherent in the structure of higher education; as an educator, I work to deconstruct those barriers in my own classroom by implementing accessible teaching practices into my course design. However, though the term accessibility is often rooted in disability, I find university classrooms can be inaccessible to both disabled and non-disabled students. For example, as education becomes increasingly digital, students from less affluent backgrounds may not have access to current technology. Students of color may feel shut out from a curriculum that teaches primarily white, Eurocentric texts. Our classrooms are increasingly populated with ESL learners and students with varying cultural experiences that challenge our vision of the “average” student. I believe that all of these circumstances warrant a deep commitment to inclusive teaching that can be effectively addressed through reflective, accessibility-centered pedagogy.

My approach to teaching is guided by three main beliefs, which I will explore below. These beliefs are at the core of each decision I make in my classroom, from how to distribute course documents to the intricacies of assessment. They stem from my work in Disability Studies and Universal Design in Learning, helping to facilitate a more inclusive and accessible classroom environment.

Accessible teaching is good for all students.

Understanding the embodied experience of each student in my classroom has led me to prioritize more adaptable and accessible teaching practices to account for the variety of ways that students encounter and learn material in the classroom. While my approach is frequently motivated by disability-forward thinking that prioritizes accessibility, often I find that accessible teaching really just good teaching. My accessible teaching practices draw explicitly on Universal Design in Learning to rethink communication, assessment, and engagement. My work with UDL has led me to implement several classroom practices that serves students of all backgrounds For example:

Communication: I provide accessible, digitized class materials at the point of instruction for all students. This allows students with disabilities and language barriers to better follow along in class, but also allows other students to better absorb and reflect on class material. It even helps student athletes who needed to miss class for tournaments to remain up to date and engage with class activities and discussion.

Assessment: I offer multiple ways for students demonstrate competency on a given learning objective, including class participation, formal presentations, papers, digital projects, etc. Students take advantage of these opportunities sometimes for accessibility reasons and other times because the diverse options allow them to explore their arguments in new and generative ways. For example, in Spring 2019, a student wanted to explore the different social stigmas around suicide in our work on Virginia Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway. Rather than writing a paper, the student completed a digital project—a mock Instagram for Septimus Smith as though he were a veteran of the Iraq War. Using social media, she was able to rewrite the end of the novel as a commentary on the increased effectiveness of digital support groups and social media outreach for mental health.

Engagement: I provide multiple, public and confidential, opportunities for reflection and feedback throughout the semester, which allow students to share their confusion and opinions on course concepts without pressure or shame and allows me to respond thoughtfully to each student. I began this practice as a safe way for students to disclose their accessibility needs to me before presenting formal accommodation letters. However, in various semesters, non-disabled and/or minority students have used these opportunities to ask difficult questions they felt uncomfortable asking the class or to identify other life circumstances that impact their learning (i.e. if they are commuter students, responsible for childcare, working at jobs off campus, etc.).

Students and educators interact with the learning environment as both a physical and an ideological space.

Stemming from own identity as a person with a disability, I believe that the classroom is first and foremost a physical space which educators and students encounter in bodies that are themselves intensely physical, political, and personal. A student’s learning experience cannot be detached from their physical experience of the world and of their learning environment. As an educator, I see it as my responsibility to acknowledge and adapt to the various life experiences that my students bring with them to the classroom. This begins on the first day of the class with a syllabus containing a territorial acknowledgment, a policy on personal pronouns, and information on campus resources like the Office of Disability Services, the Writing Center, and the Counseling Center. Further, these practices extend into the content and teaching methods I employ throughout the semester where I include frequent lessons and readings on identity formation and embodiment to help students recognize their own subjectivity as part of the campus community.

In my First-Year English classes at Marquette Unversity and in Multimodal Composition at the University of Jamestown, for example, I include a unit on multimodal literacy where students analyze the physical campus as a multimodal text in the context of Accessibility, Inclusivity, and Usability. These units encourage students to explore how identity is informed by social environments as students are asked to evaluate how certain campus spaces may seem isolating for students of different social, cultural, and/economic backgrounds. Part of these units also involves exploring their own relationships to the physical spaces of higher education and how those relationships might impact their educational experience. The “Campus Spaces Unit” extends the conversations of inclusion that I have on the first day of class into the students’ everyday experiences, encouraging them to think critically about their own identities and about those of other people they interact with in the classroom.

Accessibility and inclusion are transferrable skillsets.

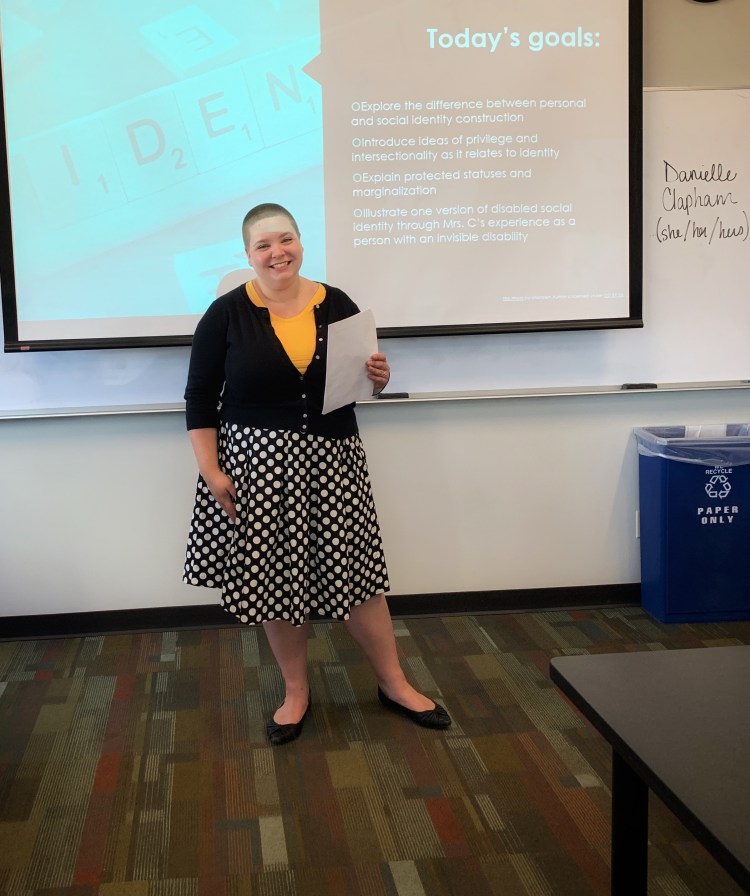

I treat accessibility and inclusion as not merely part of my philosophy as an educator, but also part of my learning objectives in each class. I want each of my students to leave my classroom with a better understanding of their own identities and ways they can ethically and responsibly make the world more inclusive for others. To that end I am committed to modeling accessible and inclusive practices for my students, often explaining why I make certain choices in the classroom to encourage them to do the same. As with acknowledging each student’s individual experience, this work begins on the first day when I introduce my syllabus. For example, in addition to talking about my policies on inclusive language, I give my own pronouns at the top of my syllabus, on the board, and in my email signature. Likewise, when I talk about formal accommodations for disabilities, I “come out” to my students as a person with a disability and talk about my own accommodations to model self-advocacy. Throughout the semester, I become increasingly explicit in scaffolding accessible and inclusive practices, telling students why I make certain choices in assignments (i.e. why due dates are often fluid or rubrics are available in multiple formats) and how I design documents to show students how inclusion is more than just lip-service and should be extended into all areas of the environment.

Of course, this also means acknowledging how inclusion is an ongoing learning process; sometimes things go wrong. Just as I model the strengths of my own inclusive practices, I am equally forthcoming about the moments when I fail at being inclusive (i.e. when I don’t consider how certain students may be affected by course content or fail to provide accessible documents in time for them to be used). By modeling moments of failure and vulnerability as well as moments of success I hope to show students how to integrate more equitable practices into their own work and how to treat inclusion as a perpetual learning process. Accessibility is never yes-or-no but rather more-or-less.

These core beliefs are at the heart of my teaching. Motivated by my own experiences of disability in higher education and my commitment to accessibility in my research and service, I believe these principles provide a strong framework for students to understand their own relationships to education and to the world.

Recent Courses

ENGL 101: Expository Writing

Fall 2020-present

ENGL102: Argumentative Writing

Spring 2022-present

ENGL314: Rhetoric of Social Movements

Spring 2021

ENGL414: Multimodal Composition

Spring 2022-present

ENGL190: Popular Literature and Analysis

Fall 2021

ENGL370: Images of Woman in Literature

Spring 2024

Sample Syllabi & Evaluations

Related Research

“Usable Knowledge, Usable Skills: A Model of Rhet/Comp and Library Collaboration to Support Student Content-Creation in the Multimodal Classroom”

Midwest Modern Language Association Conference, November 2022

“Better Together: Libraries and Writing Centers as Collaborative Partners”

North Dakota Library Association Annual Conference, October 2021

“Resisting the Retrofit: Reimagining the First-Year Classroom as a Disability-Centered Space through Universal Design”

Conference on College Composition and Communication, March 2020 (Conference cancelled due to COVID-19 pandemic)

“Space for Every Body: Reading for Access and Inclusion in the First-Year Writing Classroom” “Beyond Compliance: Creating Inclusive Classrooms for Students with Disabilities”

Writing Innovation Symposium, Spring 2018

“Teaching Research: Integrating Library Resources into the FYE Curriculum”

Interdepartmental Panel, Marquette University, Fall 2015